You need to choose between two 18-inch isolation valves for a high-pressure crude oil pipeline: a gate valve costing $8,500 or a ball valve at $32,000. Which one should you pick?

The price gap is big, but choosing the wrong valve can cost even more. I’ve seen projects lose over $140,000 on oversized ball valves and $250,000 in lost production from picking the wrong type.

In my 20 years of specifying valves for refineries, chemical plants, and offshore platforms, I’ve handled over 500 gate valve and 800 ball valve projects. I’ve tracked failures, measured performance, and calculated real costs. This guide explains when to use gate or ball valves, how the economics change at 12 inches, and what failure issues you’ll see in oil, gas, and chemical plants.

Gate Valves

What is a Gate Valve?

Gate valves are linear-motion shut-off valves that use a sliding wedge (the “gate”) moving perpendicular to the flow path. As the handwheel or actuator turns, the stem raises or lowers the gate to open or close the flow passage.

How Gate Valves Operate

Gate valves operate through multi-turn actuation. A typical 8″ gate valve requires 30-45 seconds to travel from fully closed to fully open. Large 24″ valves take 2-3 minutes to operate.

Two main stem designs exist:

Rising stem gate valves let you see the stem position because the stem moves up as the valve opens. This design needs vertical space, usually 24 to 36 inches above the valve, but gives you a quick visual check of whether the valve is open or closed.

Non-rising stem gate valves keep the stem inside the valve body. The gate travels up and down the threaded stem as it rotates. These work in tight spaces but require position indicators to show open/closed status.

Variations & Configurations

Gate valves come in three primary designs based on the wedge configuration:

Solid wedge gate valves use a one-piece wedge that provides maximum strength. We use these for high-pressure applications up to 2500# class. The solid design handles thermal expansion well, but can bind if temperature changes occur when the valve is closed.

Flexible wedge gate valves have a cut that allows flexing, reducing binding while maintaining good sealing. These are common for steam service with large temperature swings.

Parallel slide gate valves use two discs and a spring for good low-pressure sealing and slurry handling, making them favored in chemical plants for corrosive service.

Knife gate valves are a specialized type with a sharp-edged gate that cuts through thick slurries and solids. Wastewater treatment and mining operations rely on these, but they’re less common in oil & gas.

Performance Characteristics

Gate valves cause very little pressure drop when fully open, usually 0.5 to 1.0 psi for an 8-inch valve at 500 GPM. Their full-bore design means the flow path is the same size as the pipe, with nothing blocking it.

This low pressure drop is very important in long pipelines. For example, a 50-mile crude oil pipeline with 20 isolation valves can save $15,000 to $25,000 per year in pumping costs compared to using reduced-port ball valves, which each cause a 3 to 5 psi drop.

When to Use Gate Valves

Gate valves excel in these applications:

- Large diameter pipeline isolation (12″ and above) – Refineries, petrochemical plants, crude oil gathering systems

- Infrequent operation – Main line isolation valves operated 2-10 times per year during turnarounds

- Minimal pressure drop requirements – Long pipelines, gravity-fed systems, low-head pump systems

- Budget-constrained projects – Municipal water, power generation, cooling water, industrial cooling loops

- Full-bore flow applications – Pipeline pig launchers/receivers, systems intolerant of any flow restriction

- Slurry service with large solids – Knife gate valves for mining, wastewater, pulp & paper

- High-temperature steam – Power generation, refinery steam systems above 800°F

- Non-critical isolation duty – Tank farm piping, process water systems, firewater lines

Ball Valves

What is a Ball Valve?

Ball valves are quarter-turn rotary valves that use a spherical closure element with a cylindrical bore through the center. When the ball rotates 90 degrees, the bore aligns with or blocks the flow path.

How Ball Valves Operate

Ball valves operate on a quarter-turn, opening or closing in 2 to 5 seconds, regardless of size. A lever, gear operator, or automated actuator turns the ball 90 degrees between open and closed.

Two primary ball support designs exist:

Floating ball valves (sizes 1/2″ to 12″) suspend the ball between upstream and downstream seats. Line pressure pushes the ball against the downstream seat, creating a tight shutoff. These work up to Class 600 in sizes below 6″, but pressure limitations kick in above that.

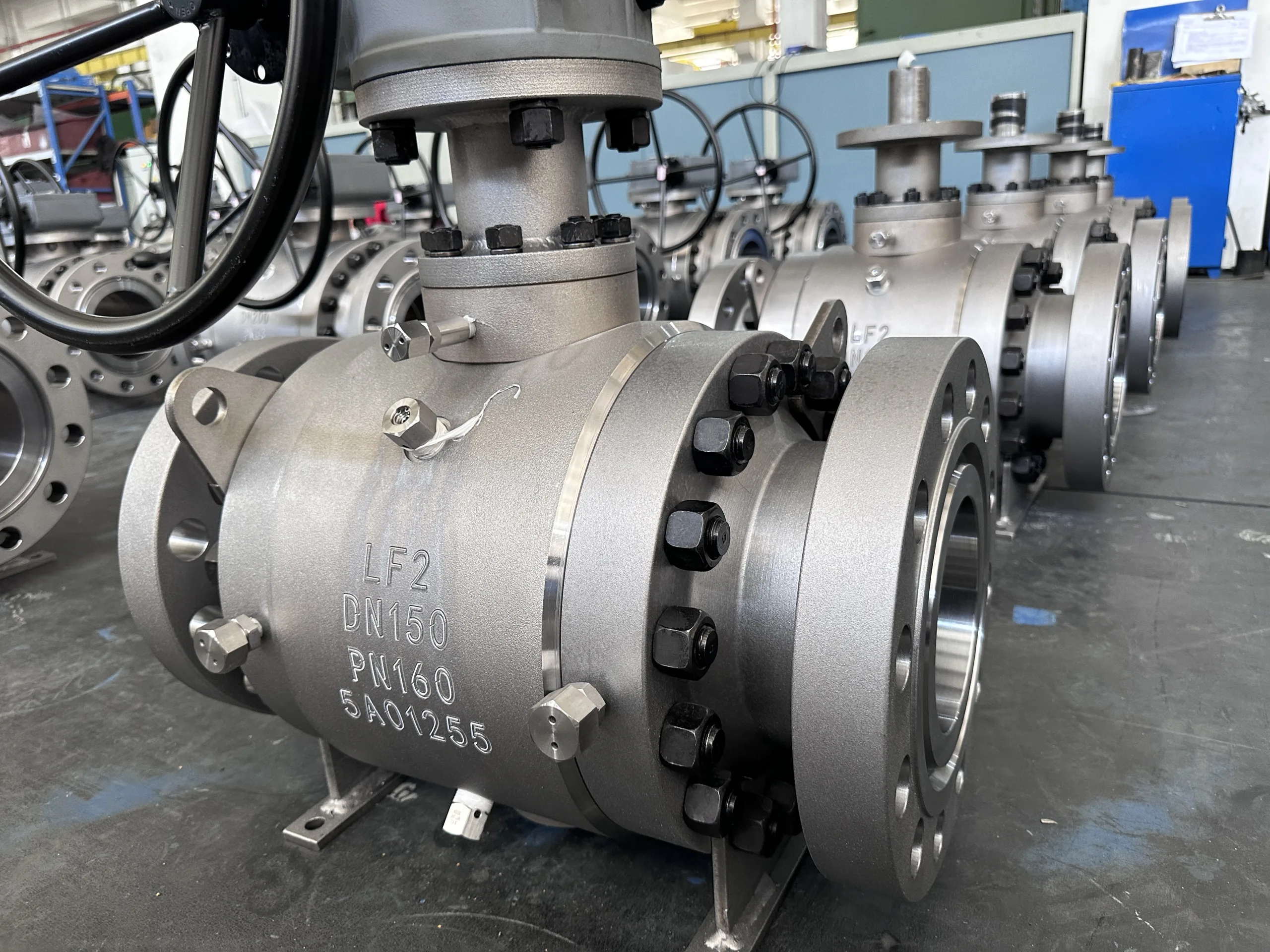

Trunnion-mounted ball valves, which range from 6 to over 60 inches, use a fixed shaft at the top and bottom to support the ball. Thrust bearings take on the pressure loads. This design can handle high pressures, up to 2500# class, and large sizes, but it costs 200 to 400 percent more than floating ball designs.

Comparative Advantages

Ball valves provide several advantages over gate valves:

Ball valves open and close quickly, making them ideal for emergency shutdowns. In critical situations, their rapid action can prevent costly losses that slower gate valves can’t.

Tight sealing reaches Class VI shutoff (bubble-tight) with soft seats. Gate valves typically achieve Class IV or V (minimal but measurable leakage). For fugitive emissions compliance in VOC service, ball valves reduce regulatory risk.

Ball valves are compact and don’t need extra vertical space. An 8-inch ball valve weighs 95 pounds, while a similar gate valve weighs 185 pounds. This 50 percent weight savings is helpful for offshore platforms and skid-mounted systems.

Ball valves last 10,000 to 50,000 cycles before the seats need to be replaced. Their self-lubricating PTFE or RPTFE seats don’t wear out from repeated use like the metal-to-metal contact in gate valves.

Limitations & Trade-offs

Ball valves face significant limitations in specific applications:

Costs rise quickly for ball valves larger than 12 inches, making them too expensive for many uses. For example, a 24-inch Class 300 ball valve costs $45,000 to $75,000, while a similar gate valve costs $12,000 to $18,000. This three- to six-times price difference is due to the need for a trunnion-mounted design in large ball valves.

For sizes above 12 to 16 inches, the ball is too heavy for the seats to support under pressure. Floating ball designs can’t handle this and may fail. Trunnion-mounted ball valves need extra parts like thrust bearings, support shafts, and precise machining, which all add to the cost.

Reduced-port ball valves cause a pressure drop of 3 to 5 psi, while gate valves only drop 0.5 to 1 psi. Full-port ball valves avoid this problem but cost 30 to 50 percent more than reduced-port types. In long pipelines, the extra pressure drop can mean thousands of dollars more in yearly pumping costs.

Ball valves have temperature limits that restrict their use in extreme conditions. Most ball valves with PTFE seats can only handle up to 450°F. Metal-seated ball valves can go above 1000°F, but they cost three to five times more than standard soft-seated versions and don’t seal as tightly.

When to Use Ball Valves

Ball valves excel in these applications:

- Emergency shutdown (ESD) systems – Chemical plants, refineries, offshore platforms requiring fast closure

- Frequent cycling applications – Batch processes, automated control, flow switching (>100 cycles/year)

- Tight sealing requirements – Fugitive emissions compliance (EPA LDAR programs), toxic/hazardous services

- Small to medium line sizes – 1/2″ to 12″ diameter, where economics favor ball valves

- Automated operation – Quarter-turn reduces actuator size and cost (80 ft-lbs vs 350 ft-lbs for gates)

- Space-constrained installations – Offshore platforms, skids, retrofit applications with limited vertical clearance

How Are Gate Valves & Ball Valves Similar?

Gate valves and ball valves share several fundamental characteristics. Both are:

- Isolation valves designed for fully open or fully closed service (not throttling or flow control)

- Bi-directional shutoff valves that seal flow from either direction

- Available in the same pressure classes (150# through 2500#) per ASME B16.34

- Manufactured in identical materials (carbon steel, 316 stainless steel, chrome-moly, duplex alloys, exotic alloys)

- Compliant with the same industry standards (ASME B16.34, API specifications, NACE MR0175 for sour service)

- Used across the same industries (oil & gas, chemical processing, power generation, water/wastewater)

- Subject to the same maintenance requirements (periodic testing, seat inspection, stem seal replacement)

- Available with manual, gear, or automated actuation (pneumatic, electric, hydraulic)

- Offered with fire-safe certification (API 607/6FA for ball valves, API 6FB for gate valves)

How Are Gate Valves & Ball Valves Different?

Although both types are used for isolation, gate valves and ball valves operate in very different ways, resulting in distinct performance characteristics.

Ball Valves Compared to Gate Valves

Compared with gate valves, ball valves are:

- About 90 times faster to operate: 2 to 5 seconds for a quarter-turn, compared to 30 to 180 seconds for multi-turn gate valves.

- Tighter sealing – Class VI (bubble-tight) versus Class IV-V (minimal measurable leakage)

- More compact and lighter – 50% weight reduction, no vertical clearance needed for rising stems

- Better for high-cycle service – 10,000-50,000 cycle life versus 2,000-5,000 for gate valves

- Lower operating torque – 80-120 ft-lbs versus 250-400 ft-lbs for the same size (pressure-independent for ball valves)

- 3-6× more expensive in large sizes – Cost delta increases exponentially above 12″ diameter

Gate Valves Compared to Ball Valves

Similarly, gate valves are:

- Significantly cheaper in large sizes – 50-75% cost savings for 16″+ diameters

- Lower pressure drop when fully open – 0.5-1 psi versus 2-5 psi for reduced-port ball valves

- Better suited for infrequent operation – Total cost of ownership advantage when cycled <50 times/year

- Capable of knife-edge designs – Cut through slurries and solids that would jam ball valves

- Higher maintenance frequency – Stem packing adjustment every 2-3 years, seat refacing every 5-7 years

- Slower to operate – Multi-turn design requires 30 seconds to 3 minutes, depending on size.

- More prone to fugitive emissions – Exposed rising stem packing versus enclosed ball valve stem seals.

Gate Valve vs Ball Valve: Side-by-Side Comparison

Here’s how gate valves and ball valves measure up across key performance criteria:

Operation Speed | Multi-turn: 30-45 sec for 8″, 2-3 min for 24″ | Quarter-turn: 2-5 sec regardless of size |

Sealing Performance | Class IV-V (minimal leakage, not bubble-tight); metal seats age and wear; bi-directional | Class VI (bubble-tight with soft seats); maintains tight shutoff for years; bi-directional. |

Pressure Drop (Fully Open) | Minimal: 0.5-1.0 psi for 8″ at 500 GPM; full-bore flow path equals pipe diameter | Full-port: 1-2 psi; Reduced-port: 3-5 psi (disc partially obstructs flow even when open) |

Size Range Economics | Cost-effective 12″+; 24″ gate $12K-18K vs ball $45K-75K (3-6× savings) | Economical 1/2″ to 12″; above 12″, trunnion mounting increases costs exponentially |

Maintenance Frequency | Packing adjustment every 2-3 years ($350 parts + labor); Seat refacing 5-7 years ($1,200-2,500) | Seats 5-7 years infrequent service, 3-5 years high-cycle ($180-400); Stem seals 5-7 years ($80-150) |

Common Failure Modes | Stem packing leaks (45%); Seat erosion from throttling (25%); Stem thread galling (15%); Bonnet leaks (10%); Body cracks (5%) | Seat compression/wear (50%); Stem seal leakage (20%); Actuator/gear failures (15%); Water hammer cracks (10%); Stem seizing (5%) |

Operating Torque | Moderate-high: 250-400 ft-lbs for 8″ (increases with line pressure and age) | Low: 80-120 ft-lbs for 8″ (constant regardless of pressure; ball floats or uses bearings) |

Weight / Installation | Heavy: 8″ Class 300 = 185 lbs; Requires 24-36″ vertical clearance for rising stem | Lighter: 8″ Class 300 = 95 lbs (50% less); Compact, no vertical clearance required |

Service Life (Cycles) | 2,000-5,000 cycles (designed for infrequent isolation); throttling reduces lifespan 80% | 10,000-50,000 cycles (designed for high-cycle automated service) |

Typical Cost (8″ Class 300) | Carbon steel: $2,800-4,200; 316SS: $8,500-12,000 | Carbon steel: $4,500-6,800; 316SS: $12,000-18,000 (30-50% more) |

Standards Compliance | API 600 (Steel Gate Valves), MSS SP-70, ASME B16.34, API 6FB (Fire-safe) | API 6D (Pipeline Valves), API 608 (Metal Ball), API 607/6FA (Fire-safe), ASME B16.34 |

Temperature Range | -20°F to 1000°F depending on materials (WCB, CF8M, WC9); metal seats handle extremes | PTFE seats: -40°F to 450°F; Metal seats: -320°F (LNG cryogenic) to 1000°F+ (3-5× cost premium) |

Fugitive Emissions | Higher risk: exposed rising stem packing requires periodic adjustment; 500+ ppm leaks are common after 3 years. | Lower risk: enclosed stem seals last 5-7 years; better EPA LDAR compliance (typically <100 ppm) |

Best Applications | Large pipelines 12″+; infrequent isolation; minimal pressure drop critical; budget-constrained projects; slurry with solids | ESD systems requiring fast closure; frequent cycling >100×/year; tight sealing; automated control; compact installations |

A key lesson from 20 years of field data: gate valves usually fail because of missed maintenance, like packing adjustments, while ball valves fail from wear due to frequent cycling. This shows the best uses for each—gate valves for infrequent, cost-sensitive isolation, and ball valves for high-cycle situations where speed and reliability are essential.

Gate Valve or Ball Valve? Key Considerations

If you’re not sure which valve would be best suited for your system, an experienced valve engineer can guide you toward the right solution based on your specific operating conditions, budget, and maintenance capabilities.

There are exceptions to every rule, but these decision frameworks cover 90% of industrial applications in oil & gas and chemical processing:

Choose Gate Valve If:

- Line size exceeds 12″ diameter – Cost advantage becomes significant and grows with size (24″ ball costs 3-4× more than gate)

- Minimal pressure drop is critical – Full-bore gate provides 0.5-1 psi versus 2-5 psi for reduced-port ball; saves thousands in annual pumping costs on long pipelines.

- Operation frequency is low – Less than 50 cycles per year (typical isolation service during shutdowns, turnarounds, or emergencies)

- Budget is constrained – Municipal water systems, power generation, cooling water, and industrial process water, where capital cost drives decisions.

- Full-bore flow is required continuously – Pipeline pig launchers/receivers, systems with zero tolerance for flow obstruction.

- Slurry service involves large solids – Knife gate valves cut through solids that would jam ball valves; common in mining and wastewater treatment.

- Existing infrastructure uses gate valves – Standardization benefits (spare parts inventory, technician training, maintenance procedures)

- Slow, controlled closure is acceptable or preferred. Multi-turn operation provides an inherent “soft close” that prevents water hammer.

Specific decision thresholds from field experience:

IF size ≥ 16″ AND operation < 50 cycles/year → Gate valve saves 40-70% capital cost

I reviewed a refinery crude unit specification in 2017 calling for 6×18″ ball valves at isolation points. The engineer assumed “modern plants use ball valves.” The quoted ball valve cost is $32,000 each, for a total of $192,000. I checked the operating parameters: isolation duty only, operated 2-3 times per year during turnarounds. No need for fast operation. Gate valves provided the required minimal pressure drop with 1/4 the capital cost. We switched to 18″ gate valves at $8,500 each = $51,000 total. Savings: $141,000 on initial purchase. Over 7 years, including maintenance, gate valves still cost $140,000 less than ball valves would have.

IF pressure drop budget < 1.5 psi AND flow is continuous → Gate valve advantage

Choose Ball Valve If:

- Fast operation is required – Emergency shutdown (ESD) systems, safety interlocks requiring 2-10 second closure to prevent runaway reactions or overpressure.

- Frequent cycling occurs – More than 100-200 cycles per year (batch processing, automated flow switching, process control applications)

- Tight sealing is mandatory – Class VI bubble-tight shutoff needed for fugitive emissions compliance (EPA Method 21 < 500 ppm), toxic service, or volatile organic compounds (VOCs)

- Line size is 12″ or smaller – Economic range where ball valves compete favorably on total cost of ownership.

- Automated operation is needed – Quarter-turn requires smaller, cheaper actuators (typical 8″ ball valve: 80 ft-lbs vs 350 ft-lbs for gate)

- Installation space is limited – Compact design with no vertical clearance requirement; critical for offshore platforms, skid-mounted systems, retrofits.

- A lower maintenance budget exists: seats last 5-7 years in on/off service with minimal intervention; stems require less frequent adjustment than gate valve packing.

- Fire-safe certification is required – API 607/6FA testing is standard for ball valves; the valve proves it maintains shutoff integrity during and after fire exposure.

Specific decision thresholds from field experience:

IF cycle frequency > 200 cycles/year → Ball valve maintenance costs become lower despite higher purchase price

IF the emergency closure time < 10 seconds is safety-critical → Ball valve with actuator is the only viable option

We installed automated ball valves on a polymer processing plant reactor feed lines after the previous facility experienced a catastrophic runaway event. The old gate valves required 45 seconds to close (multi-turn handwheel operation). During the runaway, pressure built faster than the operator could close the valve. The pressure relief valve lifted, venting $250,000 of product to the flare. The new ball valves close in 3 seconds via pneumatic actuators. When we tested the emergency shutdown system, the ball valves stopped reactant flow before pressure exceeded the normal operating range. For emergency shutdown systems, API 6D specifies ball valves for exactly this speed requirement.

IF fugitive emissions must stay < 500 ppm per EPA Method 21 → Ball valve stem seals provide better long-term compliance

An offshore platform used 8″ gate valves for crude oil service. After 3 years, the stem packing degraded, and EPA/LDAR monitoring detected a hydrocarbon leak exceeding 500 ppm. Environmental fine: $15,000. Emergency offshore repack: $8,000. Ongoing monitoring increased to monthly: $3,000/year additional cost. Gate valves have exposed rising stems with packing requiring periodic adjustment every 2-3 years. Ball valves use enclosed stem seals that typically last 5-7 years, providing more predictable performance and fewer fugitive emissions violations.

FAQ

What is the main difference between a gate valve and a ball valve?

The main differences are the closure mechanism and operating speed. Gate valves use a sliding wedge that moves perpendicular to the flow, requiring multi-turn operation (30-60 seconds for 8″ valves, 2-3 minutes for 24″ valves). Ball valves use a rotating sphere with quarter-turn operation (2-5 seconds regardless of size). Gate valves provide minimal pressure drop in large sizes but require more maintenance. Ball valves seal tighter and cycle more reliably, but cost significantly more above 12″ diameter due to trunnion-mounted construction requirements.

The secondary difference is cost economics. Below 12″ diameter, ball valves cost 30-50% more but often justify the premium through lower maintenance and longer cycle life. Above 12″ diameter, ball valves cost 200-400% more than gate valves (a 24″ ball valve runs $45,000-75,000 versus $12,000-18,000 for an equivalent gate valve), making gates the economical choice for infrequent isolation duty.

Are ball valves better than gate valves?

Ball valves are not universally “better”—each excels in specific applications based on size, cycle frequency, and operating requirements. Ball valves provide faster operation (2-5 sec vs 30-180 sec), tighter sealing (Class VI vs Class IV/V), longer cycle life (50,000 vs 5,000 cycles), and lower operating torque. However, gate valves cost 40-70% less for sizes above 12”, create lower pressure drop when fully open (0.5-1 psi vs 2-5 psi), and offer better total cost of ownership for infrequent operation.

Choose ball valves when you need fast operation for emergency shutdown systems, frequent cycling for automated batch processes, tight shutoff for fugitive emissions compliance, or compact installation in space-constrained locations. Choose gate valves when you need minimal pressure drop in large pipelines, have budget constraints, operate infrequently (less than 50 cycles/year), or require full-bore flow with zero obstruction.

For a 24″ pipeline isolation valve operated twice yearly during maintenance shutdowns, a gate valve costs $14,000 versus $65,000 for a ball valve. The gate valve’s slower operation (2-3 minutes vs 10 seconds) doesn’t matter for this application, making it the better economic choice. For an 8″ emergency shutdown valve on a chemical reactor requiring a 3-second closure to prevent runaway reactions, the ball valve is the only viable option despite costing 50% more than a gate valve.

Can you use a gate valve for throttling (flow control)?

No, gate valves should never be used for throttling or flow control. Gate valves are designed exclusively for fully open or fully closed service. When partially open, high-velocity flow through the restriction erodes and damages the wedge seats, causing premature failure and leakage within months. For flow control or pressure regulation, use globe valves, butterfly valves, or dedicated control valves specifically engineered for throttling service.

We debugged a cooling water system where operators throttled a 12″ gate valve at 50% open to control the flow rate. After only 8 months, the valve developed a significant leak requiring emergency shutdown. When we disassembled the valve, the wedge seat showed V-shaped erosion channels approximately 1/8″ deep. The high-velocity water at 15 feet per second eroded the bronze seat material. Replacement cost: $4,200 for the valve. Production loss during emergency shutdown: $35,000. Re-engineering with a proper butterfly control valve: $18,000.

The root cause: gate valves use wedge-shaped gates that create severe turbulence when partially open. The restricted flow accelerates to 3-5× normal velocity, generating erosive forces that destroy seats designed only for static sealing in the fully closed position. The 8-month failure we saw is typical—I’ve tracked dozens of similar failures, with an average time-to-leak of 6-14 months depending on flow velocity and pressure.

Critical rule: Operate gate valves only fully open or fully closed. Never use them for throttling, flow control, or pressure regulation. The maintenance cost and downtime risk far exceed the cost of specifying the correct valve type initially.

Which valve lasts longer in high-cycle service?

Ball valves last significantly longer in high-cycle service. Ball valves are designed for 10,000-50,000 operating cycles before requiring seat replacement, while gate valves are designed for 2,000-5,000 cycles before seat refacing becomes necessary. Ball valves use self-lubricating seats (PTFE, RPTFE, or PEEK polymers) that don’t wear significantly from repeated 90-degree rotation. Gate valves use sliding metal-to-metal or metal-to-elastomer seat contact that generates wear with each stroke, particularly if debris or scale is present in the system.

For automated applications with more than 500 cycles per year, ball valves provide 5-10× longer service life between major maintenance events. A chemical plant batch process operating a ball valve 1,000 times per year can expect 10-15 years before seat replacement ($180-400 parts + 2 hours labor). The same duty would wear out a gate valve in 2-3 years, requiring seat refacing ($1,200-2,500 machine shop work + 6-8 hours labor + valve removal/reinstallation).

The cycle life difference stems from fundamental design differences. Ball valves rotate a smooth sphere against resilient polymer seats—minimal friction, no sliding wear, self-cleaning action. Gate valves slide a metal wedge against seats under load—high friction, abrasive wear, debris can scratch seating surfaces. Every gate valve cycle generates microscopic wear. After 2,000-5,000 cycles, the accumulated wear creates leakage paths.

However, for infrequent isolation duty (less than 50 cycles per year), both valve types last for decades before requiring major maintenance. A gate valve operated 10 times per year reaches its 2,000-cycle design life after 200 years—far exceeding the facility’s operational lifetime. In this service, gate valves’ lower purchase cost (50-75% less for sizes above 12″) makes them economically superior despite theoretically shorter cycle life. The key is matching valve cycle capability to actual service requirements—don’t pay for 50,000-cycle ball valve capability when your application only needs 500 cycles over the valve’s entire service life.

Conclusion

Gate valves and ball valves both provide reliable isolation when their designs are matched to your system’s operating parameters, cycle frequency, and budget constraints. Gate valves deliver minimal pressure drop and low capital cost in large sizes (12″+), making them ideal for infrequent isolation in pipelines, tank farms, and process water systems. Ball valves provide fast operation, tight sealing, and high cycle life, making them essential for emergency shutdown systems, automated batch processes, and fugitive emissions-sensitive applications.

The most common mistake is choosing ball valves for large, rarely used isolation jobs where gate valves would work just as well for 40 to 70 percent less cost, or using gate valves in high-cycle service where they’ll fail in 2 to 3 years instead of the 10 to 15 years you’d get from ball valves. The right choice depends on size and how often the valve will be used, not on brand or whether the technology is new or old.

Next step: Download our free Valve Selection Decision Matrix that maps your operating conditions (size, pressure, temperature, cycle frequency, budget) to the optimal valve type and configuration. [Insert Internal Link: Valve Selection Tools]

Need help choosing valves for a critical application? Contact our technical team. We will review your P&IDs, process conditions, and operating needs to recommend the right valve setup—materials, pressure class, actuation, and accessories—for your oil and gas or chemical processing system.